If you’ve ever run a custom LCD display module project, you know the painful truth: late “small changes” rarely stay small. A good configuration-freeze plan is basically your best insurance against surprise rework, schedule slips, and endless back-and-forth during qualification.

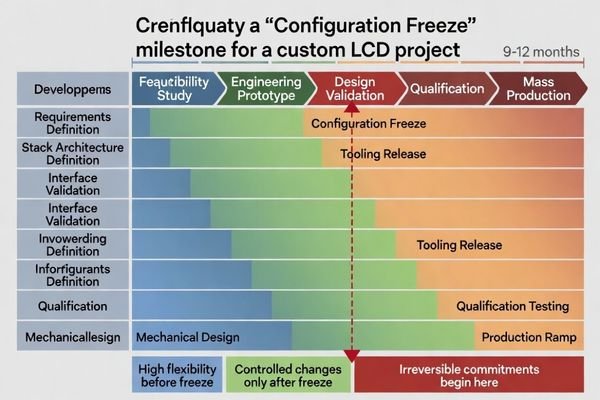

Configuration freeze is the moment you lock the buildable, testable technical “contract” for a custom LCD display module—what will be manufactured, how it must behave, how it will be measured, and how changes will be controlled. The most reliable timing is milestone-driven: freeze just before irreversible commitments (tooling, long-lead purchasing, formal qualification), then manage any later changes through strict change control and traceability to protect schedule, cost, and quality.

In my LCD display module integration work at LCD Module Pro, I’ve watched projects go off-track for one common reason: the team thought “freeze” meant “we won’t change the drawing,” while the customer thought “freeze” meant “this is exactly what we’ll receive and approve in mass production.” That mismatch is how you end up repeating samples, redoing reliability, and reopening decisions you already paid for.

I also want to be honest about something: a disciplined freeze process1 isn’t about being rigid. It’s about being smart with flexibility—push changes earlier, when they’re cheap, and make late changes rare, visible, and controlled. When you do that, the whole project feels calmer: fewer surprises, clearer ownership, and faster decisions.

What does “configuration freeze” really mean for a custom LCD display module?

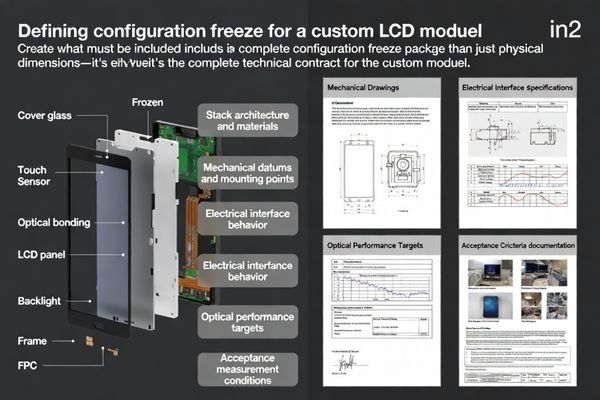

Before deciding when to freeze, you need to agree on what freeze includes—because teams often freeze the mechanical drawing but leave the behavior and acceptance rules vague, and that’s where disputes come from.

In a custom LCD display module project, configuration freeze means locking the exact technical contract manufacturing will build and the customer will validate against. It includes the stack architecture and appearance targets, the electrical interface behavior and timing assumptions, the mechanical envelope and mounting datums, any required initialization parameters (if applicable), plus the acceptance method and measurement conditions that define pass/fail. After freeze, changes require formal change control because small tweaks can cascade into tooling, yield, reliability, and qualification timelines.

From an engineering standpoint, a “frozen” configuration is a package that leaves little room for interpretation. It’s not just drawings—it’s also the *measurement reality2. If you don’t freeze how you measure and judge the module, you haven’t really frozen anything.

More Than Just a Drawing

A common trap is freezing only the 2D/3D CAD and believing the project is “stable.” In reality, the optical stack definition (panel + bonding approach + cover lens/touch layers + surface treatments, if used) and the mechanical stress path (compression windows, datums, keep-outs) are usually what drive late surprises. If those aren’t locked, you can end up with “same size, different look,” or worse, a new stress condition that changes appearance over temperature or time.

The Behavioral and Acceptance Contract

The behavioral contract matters because the host and module must agree on how the module starts, sleeps, wakes, and recovers. If the project requires a defined initialization sequence or timing assumptions (depending on interface and controller behavior), those must be version-controlled. And the acceptance contract must be enforceable: specify measurement conditions (equipment, geometry, ambient conditions, sample state), defect limits, and the golden/limit samples that define boundaries. This is the part that prevents arguments later.

When is the right time to freeze, and what milestones should trigger it?

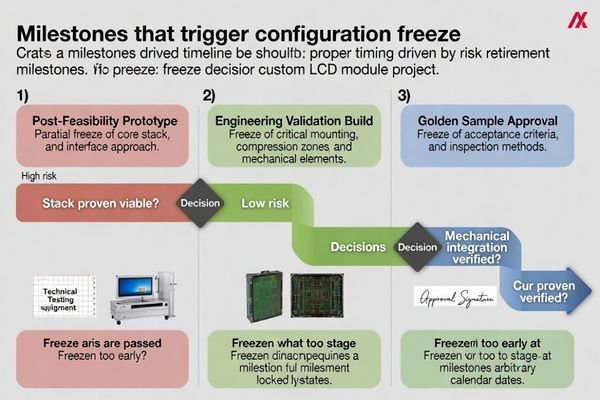

Freeze timing isn’t a calendar date—it’s a decision you earn by retiring risk. I like milestone-driven freezes because they align the “lock” to real proof, not hope.

A practical freeze timing is milestone-driven: freeze what you must to proceed to the next irreversible step, and keep the rest flexible until major risks are proven. Common triggers include verified feasibility of the stack and interface behavior, approval of an engineering prototype that matches the intended build, confirmation of critical tolerances and mounting references, and alignment on acceptance criteria and the golden/limit sample approach. If tooling, cover lens, bonding, or custom mechanics are involved, freeze should happen before committing to long-lead items—otherwise late changes become expensive and schedule-breaking.

When I work with OEM teams, the best results usually come from a phased freeze. Not everything has to lock on the same day—but the high-impact items must lock before money and time become irreversible. A simple way to think about it is: freeze the “contract” in the same order you commit real resources.

A typical sequence that works well is:

- After feasibility prototypes: freeze the core stack direction and interface approach so parallel teams can move.

- After EVT-style build proves fit and basic behavior: freeze critical mounting datums3, compression windows, and any long-lead mechanical items.

- After golden/limit samples are approved: freeze acceptance, inspection method, and cosmetic boundaries for mass production.

This keeps the program moving without pretending you know everything on day one.

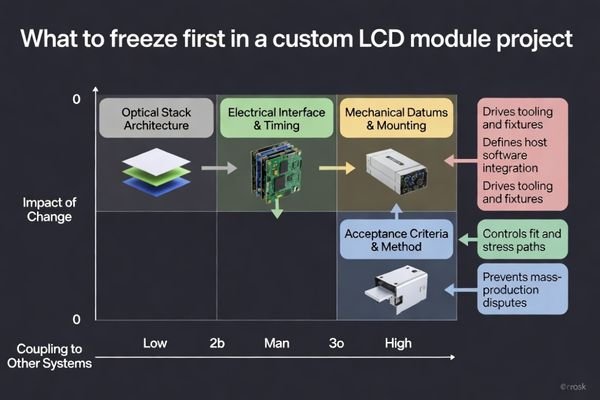

What must be frozen first to avoid rework and qualification resets?

If you only freeze one thing, freeze the items that cause “domino effects.” In my experience, resets happen when the change touches multiple domains at once—optical + mechanical + acceptance + qualification.

To prevent rework and qualification resets, freeze the highest-coupling pillars first: the stack architecture (including cover lens/touch and any surface treatment choices), the electrical interface behavior and timing assumptions, the mechanical reference datums and compression windows, and the acceptance criteria plus the measurement conditions used at incoming and outgoing inspection. These define not only performance but how performance is judged, which is where disputes start. After these are locked, improvements should be limited to process tuning within defined windows—not architectural changes that force new samples and repeated validation.

If you’re deciding priorities, here’s how I suggest reading the table: items that drive tooling, system integration behavior, and pass/fail judgment belong at the top. If those move late, qualification almost always resets.

| Item to Freeze | Why It’s Critical to Freeze First | Impact of a Late Change |

|---|---|---|

| Optical Stack Architecture4 | Defines core visual performance and often drives cover lens/bonding tooling and fixtures. | Forces material changes, tooling updates, and repeat validation for optical performance and reliability. |

| Electrical Interface & Timing | Defines host driver work, FPC design, and system bring-up behavior (startup/sleep/wake). | Triggers software changes, possible PCB rework, and re-testing of stability across state transitions. |

| Mechanical Datums & Mounting | Defines fit, alignment, and stress paths inside the enclosure (what gets compressed and where). | Can require enclosure changes, new stress validation, and re-check of environmental robustness. |

| Acceptance Criteria & Method | Establishes “definition of good” including measurement conditions and defect rules. | Causes mass-production disputes, inconsistent QC decisions, and costly containment actions. |

Freezing these pillars early lets teams work in parallel with fewer surprises. It also makes later changes easier to classify: “Is this within the process window?” or “Does this redefine the contract?”

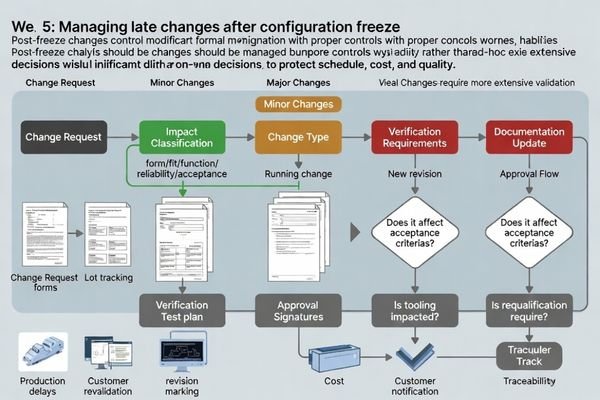

How do you manage late changes after freeze without blowing schedule and cost?

Late changes happen. The trick is to handle them like controlled engineering work—not informal tweaks that quietly invalidate prior tests.

Manage post-freeze changes with a clear change-control playbook: classify impact (form/fit/function/reliability/acceptance), define exactly what must be re-verified, and decide whether it’s a running change, a new revision, or a split build. Tie every change to updated documentation, traceability, and a targeted regression test subset so prior qualification isn’t accidentally invalidated. In practice, anything that affects appearance boundaries, interface behavior, mechanical stress paths, or acceptance rules should require customer sign-off before release.

In field debugging, I’ve seen “minor” post-freeze substitutions turn into big headaches simply because nobody tracked them properly. That’s why I like to keep the change-control language very plain: if a change can alter what the customer sees, measures, or integrates, it deserves formal handling.

The Change Control Playbook

Start by classifying the change in a way everyone understands. A low-risk change is one that clearly doesn’t touch form, fit, function, reliability, or acceptance judgment. If there’s any doubt, treat it as major. This isn’t about being conservative for the sake of it—it’s about avoiding hidden resets later when someone realizes the “small change” altered an inspection result or integration behavior.

Re-verification and Communication

For major changes, define a targeted re-verification plan5. You don’t always need to redo everything, but you do need to re-check what could realistically move. For example, a backlight component change might require re-checking brightness, uniformity, and lumen maintenance trend, while leaving shock/vibration untouched—if the mechanical design didn’t change. Most importantly, document the decision, record traceability to affected lots, and get customer sign-off before release. That’s how you protect schedule and relationships at the same time.

Product planning: choosing an LCD module approach that makes freeze easier

Some projects feel “easy to freeze,” and it’s usually because the early choices reduce coupling and leave margin. In contrast, projects designed on a knife-edge tend to freeze late—and then keep unfreezing.

A freeze-friendly LCD module plan reduces coupling and builds margin from day one. Start by locking the real use case (viewing geometry, ambient light, touch behavior, enclosure constraints), then choose a stack architecture that meets targets without relying on fragile, near-limit settings. Leave headroom in brightness, viewing angle, and interface bandwidth so production variation doesn’t force spec changes. Lock mechanical datums and compression windows early because they drive tooling and reliability. Finally, make acceptance measurable with defined test conditions, and add lifecycle protection (revision control, traceability, change notice, EOL risk review) so the frozen configuration stays stable over time.

From an engineering standpoint, the smoothest freeze happens when the plan is “boringly robust.” That usually means making a few conservative choices early so you don’t need heroic fixes later.

Build margin on purpose

I like to leave margin in the places that commonly bite teams: brightness budget at end-of-life, interface bandwidth headroom, and mechanical compression tolerance. If you’re operating everything at 100%, then any real-world variation becomes a change request. With margin, variation becomes noise you can live with.

Freeze the measurement reality early

If you do one thing differently next time, do this: lock the measurement conditions and acceptance flow early (equipment, geometry, visual grading environment, sampling rules). It’s amazing how many “technical” disputes are actually measurement disputes.

If you want support building a practical freeze plan and change-control flow for a custom module, you can reach our engineering team at LCD Module Pro via info@lcdmodulepro.com.

FAQ

Is configuration freeze the same as design freeze?

Not exactly. Configuration freeze locks the buildable and testable contract (stack, interface behavior, datums, acceptance and measurement conditions). Design work can still continue as controlled revisions inside that frozen contract.

What happens if we freeze too early?

You risk locking in choices before key risks are proven, which can trigger expensive rework later—especially for stack architecture, mechanical stress paths, and acceptance boundaries.

What happens if we freeze too late?

You delay tooling and long-lead purchasing, and you often push customer qualification out. Late changes also cost more because they ripple into yield, reliability, and schedule.

Which items most often cause qualification resets?

Changes to the stack architecture, cover lens/touch integration, interface behavior or timing assumptions, or acceptance and measurement conditions are the most common triggers for re-validation.

How do we freeze acceptance so it’s enforceable in mass production?

Define measurement conditions, equipment and geometry, defect limits, sampling/AQL, and keep signed golden and limit samples so different sites and shifts judge consistently.

Can we allow post-freeze changes without customer disruption?

Yes, if the change is clearly low-coupling and verified with a targeted regression test plus full traceability. Otherwise treat it as a new revision and get customer sign-off.

Conclusion

Defining configuration-freeze timing for a custom LCD display module project is really about controlling risk at the right moments. The best approach is milestone-driven: freeze the contract items before irreversible commitments, keep flexibility until major risks are proven, and lock measurement/acceptance so quality decisions are repeatable.

From my perspective at LCD Module Pro, the biggest wins come from freezing the high-coupling pillars early—stack architecture, interface behavior, mechanical datums, and acceptance method—then handling any later changes through strict change control with traceability and targeted re-verification. Do that well, and “freeze” stops being a stressful event and becomes the thing that makes your project predictable in cost, quality, and delivery.

✉️ info@lcdmodulepro.com

🌐 https://lcdmodulepro.com/

-

Understanding the disciplined freeze process can help you manage project changes effectively, ensuring smoother workflows and fewer surprises. ↩

-

Understanding measurement reality is crucial for ensuring accurate project specifications and avoiding costly surprises. ↩

-

Learning about critical mounting datums is essential for ensuring product fit and performance in engineering projects. ↩

-

Understanding Optical Stack Architecture is crucial for ensuring visual performance and effective tooling. ↩

-

A solid re-verification plan is essential for maintaining quality and reliability after changes, helping to avoid costly mistakes. ↩