Mixed LCD display module versions can quietly turn into a very expensive problem: receiving can’t sort them, production can’t reproduce issues, and the field starts reporting “random” failures. The cleanest fix isn’t more inspection—it’s writing revision rules into the contract so changes are visible, traceable, and controlled.

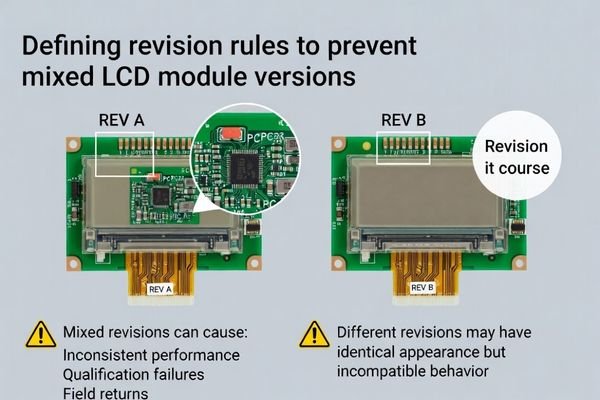

Effective revision rules in a contract create a bright-line definition of what changes trigger a new revision versus what can be a controlled running change. These rules must be tied to mandatory labeling, traceability requirements, and clear change notification clauses. By making revision control enforceable, you prevent the shipment of mixed module versions, which can cause inconsistent performance, qualification resets, and a loss of trust in the supply chain.

In my LCD display module integration work at LCD Module Pro, one of the most damaging issues a customer can face is receiving a shipment of “mixed versions1.” A line can stop because a module revision needs a different initialization behavior, or field returns can spike because a subtle stack change drifts under certain conditions.

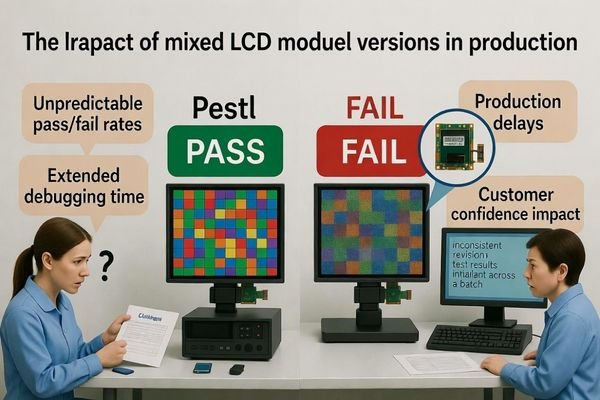

What makes it worse is how confusing it looks from the customer side: the part number matches, paperwork looks normal, and only a portion of units behave differently. In practice, the root cause is almost always a gap in how revisions are defined, identified, and enforced between supplier and customer. A strong contract closes that gap by turning “equivalent” into something measurable and by banning surprise changes from entering shipments.

How do you define revision rules in contracts to avoid mixed LCD display module versions?

If I had to summarize this in one sentence: revision rules work only when they are unambiguous, physically visible, and contractually enforceable. That means you’re not just describing change—you’re defining what the supplier is allowed to ship.

In LCD display modules, “mixed versions” usually means two or more builds that look similar on paper—but differ in behavior, appearance, or stack details—are shipped under one part number or one delivery without clear separation. A contract needs to define what counts as a revision, how revisions are identified on the product and documents, and what the supplier must do (notification, evidence, approval) before any revision can enter shipments.

From an engineering standpoint, I start by accepting a simple reality: not all changes are equal. The goal is to catch high-risk changes (the ones that can break integration or acceptance) without creating unnecessary friction for truly low-risk adjustments.

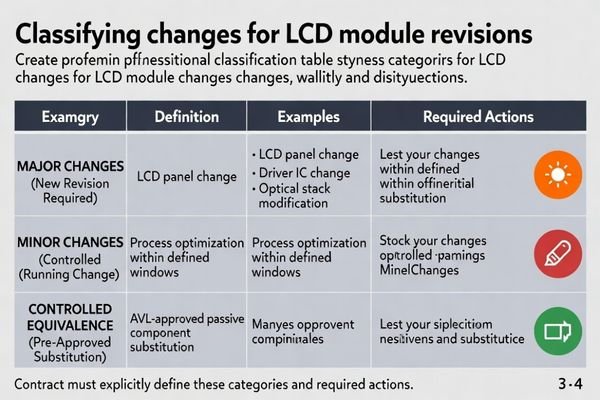

Creating a Tiered Change System2

A robust contract usually needs a tiered system. A “Major Change” is anything that could affect form, fit, function, reliability, or acceptance outcomes. That should trigger a new revision identifier, formal customer notification, and customer approval before shipment—often with a defined re-validation plan. A “Minor Change” might be a process optimization that is proven to have no external impact; those can be handled as controlled running changes if the contract says how they’re validated and how they remain traceable.

The Principle of “No Surprises”

The purpose of revision rules is a strict “no surprises” policy. The customer’s receiving team must be able to confirm, quickly and reliably, that every unit under a given part number and revision code behaves the same in all ways that matter. The contract makes that trust real by forcing transparency, traceability, and accountability—especially when the supplier wants to change something “small.”

What does “mixed versions” mean in LCD display module shipments?

Before you can prevent mixing, both sides have to agree on what “mixing” actually is. In my experience, the painful cases are rarely the obvious ones—it’s the subtle differences that slip through labeling and then show up as weird, inconsistent behavior.

In LCD display modules, “mixed versions” usually means two or more builds that look similar on paper—but differ in behavior, appearance, or stack details—are shipped under one part number or one delivery without clear separation. It can be obvious (different connector, different cover lens) or subtle (different driver IC behavior, different optical films, different backlight tuning, different initialization requirement). The real damage isn’t just rework; it’s long debug cycles because the customer can’t reproduce results consistently.

When I troubleshoot field issues, “mixed versions” is one of the first things I check—especially when a customer says, “Most units are fine, but a small percentage fail.” That pattern often points to a second build variant hiding inside a “same part number” shipment. Without clear revision marking, the customer can’t segregate the suspect units, and every test becomes noisy.

The tricky part is that “subtle” does not mean “safe.” A change in adhesive or an optical film might look identical at incoming inspection but drift after months in heat or humidity. A change in a connector/FPC vendor, grounding detail, or routing can shift EMI/ESD margin and cause intermittent issues that never show up on a calm bench test. That’s exactly why contracts must treat traceability and visibility3 as non-negotiable.

Which changes must trigger a new revision—and which can be treated as controlled equivalence?

This is where contracts either protect you or fail you. If “equivalent” is undefined, it becomes a loophole. I like to write the rule around impact, not around part category.

The contract should draw a bright line between changes that affect fit/function/acceptance risk and changes that don’t. Anything that can change interface behavior, power/reset sequencing needs, optical appearance, touch behavior, or reliability margin should trigger a new revision with customer notification and re-approval requirements. For low-risk substitutions (like equivalent passives) you can define “controlled equivalence,” but only if the supplier proves no impact using a specified regression test subset and keeps full traceability. The key is not the part category—it’s whether the change can alter customer integration, inspection outcomes, or long-term stability.

Based on the projects I support, the best way to avoid arguments is to put a clear classification table directly into the contract or quality agreement as an exhibit. It becomes the shared rulebook when a change request arrives.

| Change Category | Examples | Required Action |

|---|---|---|

| Major Change (New Revision Required) | LCD Panel, Driver IC, FPC/Connector, Optical Stack (e.g., Cover Lens, Bonding), controller configuration / initialization parameters (if applicable) | Supplier must submit a Product Change Notification (PCN) for customer approval. New revision code mandatory. Re-validation and new golden samples may be required. |

| Minor Change (Controlled Running Change) | Internal manufacturing process optimization proven to have no external impact; approved internal adjustments within defined process windows | Supplier must notify customer per contract rules (or per agreed periodic summary). No shipment mixing allowed: change must be traceable by lot/date code. Internal validation data must be available on request. |

| Controlled Equivalence (Pre-Approved Substitution) | Equivalent-spec passives from an approved vendor list (AVL) | Allowed only if explicitly defined upfront. Supplier must maintain full traceability and retain regression evidence proving no impact on function, acceptance, or reliability risk. |

The most important rule is that the customer must agree on what qualifies as “controlled equivalence4.” A supplier should never be able to decide unilaterally that a new component is “the same.” If your program needs this level of discipline, I strongly recommend defining the regression subset and documentation requirements right in the agreement. If you want help setting that up, you can contact us at info@lcdmodulepro.com.

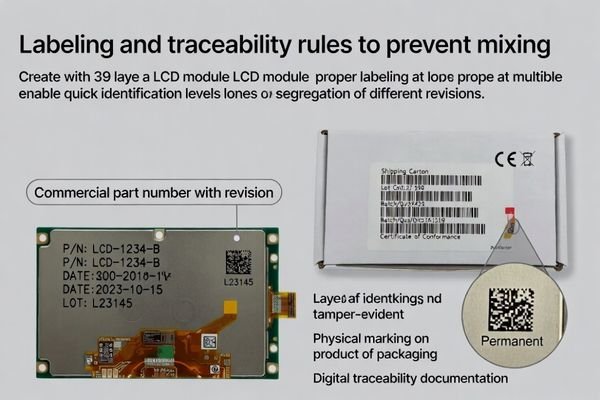

How should part numbers, labels, and traceability be written to prevent mixing?

In real life, prevention happens at receiving. If the revision isn’t visible on the box and on the unit, and if documents can’t map to shipped lots, then “revision control” is just a nice idea.

To prevent mixing, the contract should require revision visibility at three layers: (1) commercial part number rules (what changes require a new PN vs a suffix), (2) physical marking/labeling rules on each unit and carton (revision, date code, lot ID), and (3) digital traceability (COC/inspection records mapped to shipped serials or lots). Also define segregation requirements: different revisions must be packed separately, labeled clearly, and never combined in one carton unless explicitly approved. When disputes happen, the fastest resolution is always traceability—so contracts should specify how long records are retained and what data must be provided on request.

When a customer reports an issue, the first question I ask is, “What are the revision and lot codes of the failing units?” If they can’t answer, troubleshooting slows down immediately. Good contracts make these codes impossible to miss.

The Three Layers of Identification

-

Part Number (PN) and Revision Suffix: The contract must define absolute logic for identification. For example, any change affecting form/fit/function/acceptance rules requires a new revision identifier (and sometimes a new base PN), while pre-approved equivalence can remain under the same PN with strict lot traceability. The key is that the logic must be written, not implied.

-

Physical Labels: Require that every module and every shipping carton includes at least: full PN, revision code, date code, lot ID (and serial range if applicable). Receiving must be able to verify revision without guessing or opening sealed packaging.

-

Digital Traceability5: Require that each shipment includes CoC/COA data that maps the shipment to lot/date codes (and serials if applicable). Also define retention time and response expectations (what data can the customer request and how fast must it be provided).

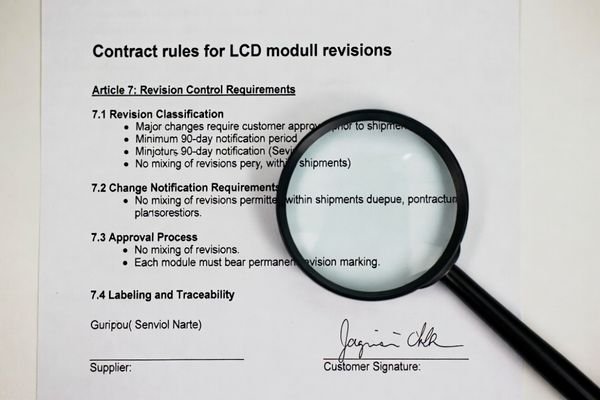

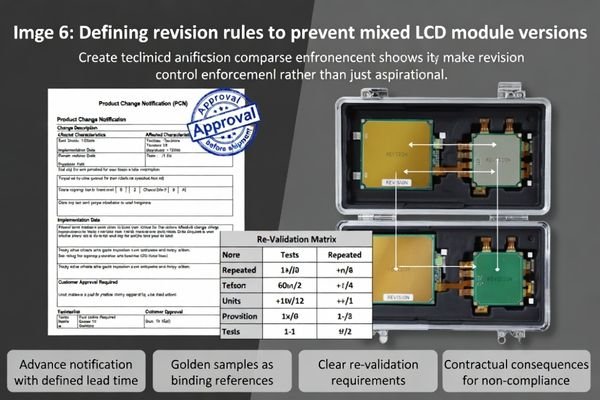

What contract clauses enforce change notification, golden samples, and re-validation?

A contract only works if it can be enforced. In my experience, the strongest agreements don’t just say “notify us”—they define lead time, evidence, approval gates, and shipment restrictions.

Acceptable revision control must be enforced through advance change notification with defined lead time, required evidence (change description, impact assessment, regression results), and clear rules on when customer approval is mandatory before shipment. The contract should tie each approved revision to golden and limit samples so acceptance doesn’t drift, and define re-validation triggers for changes that affect appearance boundaries, interface behavior, stack architecture, or reliability risk. It should also state consequences for non-compliance, including the right to reject mixed shipments and require containment and corrective action.

Creating rules is not enough; the contract needs “teeth.” If I’m helping a team draft the quality terms, these are the clauses I push to make explicit and measurable.

-

Product Change Notification (PCN) Clause: Define exactly what changes require a PCN, the minimum lead time, and what must be included (change summary, impacted characteristics, traceability plan, regression evidence). Most importantly: state that shipment of the changed revision is forbidden until written approval when approval is required.

-

Golden and Limit Sample Agreement Clause: For each approved revision, define golden samples and limit samples, stored by both parties, used as the binding reference for inspection disputes. This is the easiest way to stop “acceptance drift” over time.

-

Re-Validation Matrix Clause: A matrix is better than vague language. It defines what to re-test for each change category, so major changes don’t slip through with insufficient validation—and minor changes don’t trigger expensive, unnecessary full re-qualification.

If you’re building these clauses for a long lifecycle product, I also recommend adding explicit “no mixing” logistics language: different revisions must be segregated and clearly labeled, and any exception requires written approval and separate line items on documents. It sounds strict, but it prevents the worst surprises later.

FAQ

Is a supplier allowed to ship a new revision if performance is “equivalent”?

Only if the contract specifically defines "controlled equivalence," details the regression test data required to prove it, and ensures the new revision is still uniquely identifiable and traceable. Otherwise, it must be treated as a new revision requiring formal customer approval.

What is the fastest way to detect mixing at receiving inspection?

Mandate clear revision marking on all individual unit labels and outer shipping cartons. The receiving team should be trained to match the revision on the box label against the purchase order and the supplier’s Certificate of Conformance before accepting the shipment. Visual inspection of the modules themselves is unreliable.

Should a revision always require a new part number?

Not necessarily, but the rule must be explicitly written in the contract. High-impact changes (form, fit, function) often warrant a completely new part number, while compatible minor changes may only require incrementing a revision suffix. The key is that the identification must be unambiguous.

How do golden samples help prevent disputes about revisions?

They provide a physical, agreed-upon reference for visual and cosmetic criteria tied to a specific revision. When a supplier changes a material or process, golden samples prevent "acceptance criteria drift" by serving as the objective benchmark against which new production units are judged.

What contract lead time is reasonable for change notification?

This depends on the customer’s product lifecycle and production cadence, but 90 to 180 days is a common range for major changes. The contract should specify this minimum lead time and explicitly forbid the supplier from shipping the changed product before receiving formal customer approval.

Conclusion

To successfully avoid the costly problem of mixed LCD display module versions, revision rules must be specific, visible, and enforceable—not just “best effort.” By defining what triggers a revision, agreeing on controlled equivalence boundaries, and requiring clear labeling plus traceability, you give receiving and production the tools to keep versions separated and predictable.

In my experience at LCD Module Pro, the most stable supply relationships are the ones where revision control is treated as part of the product contract, not an informal promise. When part number logic, segregation rules, PCN lead times, golden/limit samples, and a re-validation matrix are agreed upfront, you reduce disputes, shorten debug cycles, and protect the customer’s qualification results over the full lifecycle.

✉️ info@lcdmodulepro.com

🌐 https://lcdmodulepro.com/

-

Understanding mixed versions can help prevent costly errors in module integration and ensure consistent performance. ↩

-

Understanding a Tiered Change System can enhance your approach to managing engineering changes effectively. ↩

-

Exploring this topic will highlight the critical role of traceability in preventing product failures and ensuring quality control. ↩

-

Exploring controlled equivalence helps clarify how to manage substitutions without compromising quality or reliability. ↩

-

Exploring Digital Traceability can enhance your knowledge of tracking products and ensuring quality throughout the supply chain. ↩