Standardizing on a single LCD module sounds like a quick win, yet many teams discover late that small changes in mechanics, interfaces, or front glass can trigger redesign loops and unexpected validation costs.

Yes, one LCD module model can reduce cost across several device versions when the mechanical window, connector and interface definition, and front-stack space stay consistent. The key is designing a reusable “display bay” first, then controlling variant differences through brackets, harness options, and software profiles. Validate the worst-case combination so performance and lifetime margins hold across all SKUs.

Reusing one module is rarely blocked by the display itself; it is blocked by integration drift1. A few millimeters of window change, a shifted connector, or an added cover glass layer can cascade into new brackets, different cables, firmware timing exceptions, and repeated reliability testing. Those costs often appear after the mechanical design is “mostly done,” when change is slow and expensive.

In the sections below, we break the problem into engineering dimensions that determine whether standardization pays off: what “one model” truly means, which constraints must be locked early, where hidden costs come from, how to design a platform that absorbs variation, and how to shortlist module candidates without forcing over-engineering.

What does "one LCD module model across several device versions" really mean?

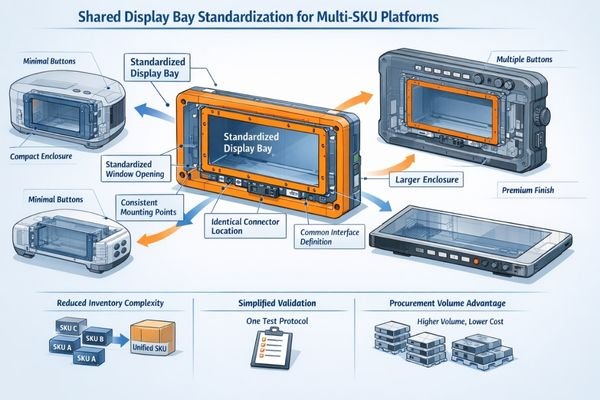

“One model for multiple versions” is not about sharing a part number at any cost. It is about ensuring the integration fundamentals stay identical, while differences move into features that do not disturb the display bay.

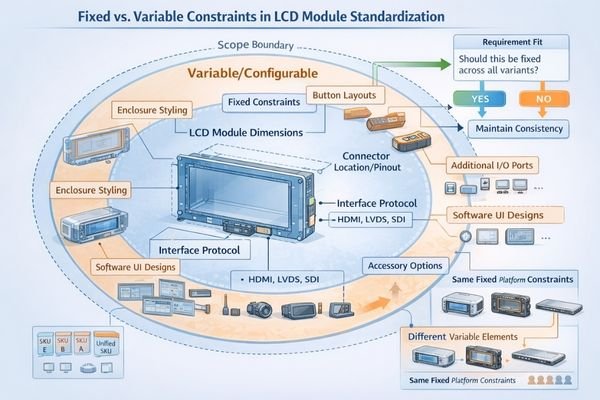

Effective module reuse means the same mechanical envelope, the same connector location and pinout, and the same electrical interface expectations, plus a front-stack space allocation that fits every variant. Differences then live outside the display bay—software settings, accessories, or enclosure cosmetics—so the module never becomes the workaround for incompatible requirements.

A good standardization effort treats the display bay like a controlled socket. The “socket” defines opening size, datum references, fastening scheme, cable routing corridor, and the interface baseline. Once that socket is stable, variants can evolve without repeatedly touching the most expensive-to-change display integration surfaces.

Mechanical Standardization

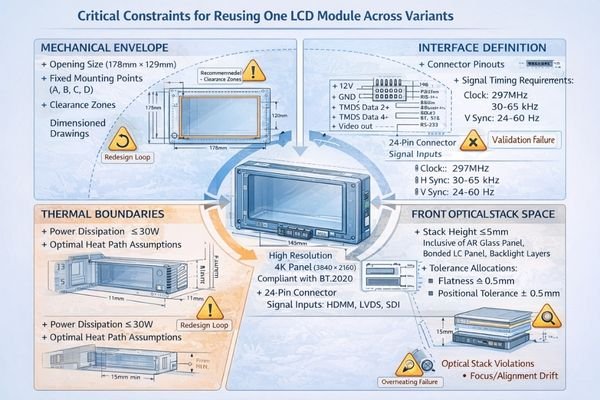

Lock the window opening, bezel overlap targets, datum references, and mounting points early, and keep them consistent across every version. If one variant changes cutout size, bosses, or stack height, you typically pay twice: first in new mechanical parts and tooling, then again in re-validation of shock, vibration, sealing, and long-term fit stability.

Interface Consistency2

Keep interface type, timing expectations, connector assignments, and power rails stable so the same firmware baseline can serve all versions. When variants demand different interfaces or pinouts, teams often create per-version harnesses and firmware branches, which multiplies test scope and increases the chance of field-only failures tied to timing, sleep/wake behavior, or power sequencing differences.

Which parameters must be fixed to reuse the same LCD module model?

The savings from reuse come from avoiding repeated mechanical and electrical work. To do that, you must freeze the parameters that drive tooling, harness definition, and qualification scope before variants start diverging.

True reuse requires four locked categories: mechanical envelope (active area, outline, datums, and mounting), interface definition (connector location, pinout, signaling, and timing), thermal boundary assumptions (backlight power budget and enclosure heat path), and front optical stack space (cover glass/touch thickness and allowable tolerances). If any category drifts, “one model” becomes bracket, harness, and re-qualification churn.

When you cannot lock all four categories, standardization can still work, but it becomes “platform reuse with controlled adapters.” The goal shifts to containing differences so they do not touch the core display socket, and so they do not introduce version-specific optical performance gaps3 or thermal derating behavior that forces different brightness limits by SKU.

Most failures happen when teams freeze the module choice but leave the bay undefined. The module then becomes the forcing function, and every variant change is paid back as redesign effort that eats the original procurement savings.

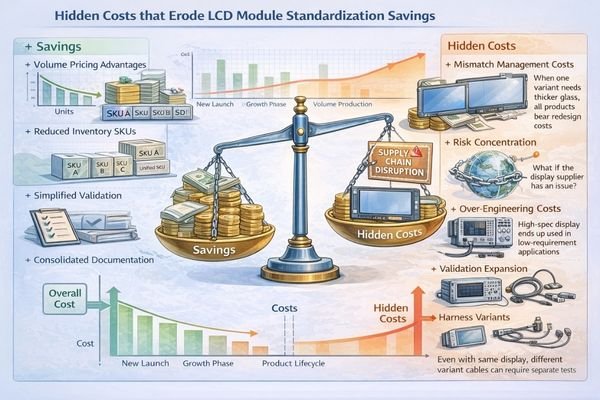

Standardization can lower unit cost, but the total cost of ownership can rise if the platform must absorb mismatched requirements. The most common hidden costs come from performance drift, validation expansion, and concentrated supply risk.

Hidden costs typically cluster in three areas: mismatch management when variants change cover glass, touch, or thermal conditions; risk concentration when one supply disruption blocks every SKU; and over-engineering when the shared module is forced to meet worst-case requirements for the entire family. These costs show up as extra tooling, harness variants, firmware exceptions, and expanded qualification cycles.

From an engineering standpoint, the trap is assuming the module is the only shared element. In reality, you share an integration stack: mechanics, optics, firmware behavior, and manufacturing controls. If one version uses thicker cover glass or a different touch stack, optical performance and brightness perception can shift; if one enclosure runs hotter, lifetime margin and dimming behavior can diverge; if the interface baseline is not stable, software work multiplies.

| Hidden Cost Area | What Triggers It | How It Shows Up | Practical Mitigation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optical mismatch | Different cover glass or touch stack | Readability differences, reflection complaints, rework loops | Reserve worst-case stack space and validate with final stack |

| Thermal divergence4 | Different enclosures and heat paths | Brightness throttling, lifetime risk, inconsistent UX | Validate worst-case enclosure and define a shared power budget |

| Interface fragmentation | Variant-specific timing or pinout exceptions | Firmware forks, longer test cycles, field-only bugs | Freeze one baseline and use configuration profiles, not branches |

| Supply concentration | Single part blocks all SKUs | Line stops, forced redesign, expediting costs | Lifecycle planning and pre-validated alternates within constraints |

If the worst-case variant drives the entire platform, you may end up paying a permanent cost premium in every unit. In that situation, splitting into two optimized modules can be cheaper overall than forcing one module to cover incompatible environments or stack-ups.

How can you design a platform so one LCD module model fits multiple versions reliably?

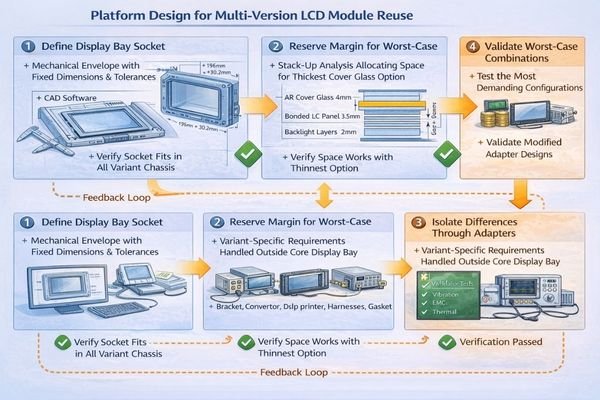

A reusable platform is built around a stable display socket that absorbs variation without changing the core bay. The objective is to keep the module integration identical while allowing controlled differences in peripherals, cosmetics, and software behavior.

Reliable platform reuse comes from four practices: define a fixed display bay socket (opening, datums, fastening, connector), reserve mechanical and front-stack space for the most demanding variant, isolate differences through adapters and configurable harness options, and validate the combined worst-case conditions. This prevents per-SKU redesign and keeps thermal and optical margins consistent across the family.

Treat the display bay as a product interface, not a component location. Document the bay like a spec: mechanical datums and tolerances, allowable stack thickness, cable routing constraints5, interface and power baseline, and acceptance criteria for readability and thermal behavior. When that spec is stable, reuse becomes repeatable rather than negotiable per variant.

Interface Socket Design

Keep the opening, datum scheme, and connector corridor identical, and use adapter brackets only outside the datum chain so they do not change the module’s reference surfaces. Plan harness options by length and strain relief without changing pinout or timing expectations. This keeps manufacturing work instructions and test fixtures stable across versions and reduces the chance of version-specific assembly escapes.

Margin Management and Worst-Case Validation

Validate the harshest combination: the hottest enclosure, the thickest front stack, and the most demanding usage pattern. Confirm that brightness limits, thermal rise, and lifetime margins remain acceptable without variant-only throttling rules. If one version must derate brightness to survive, standardization may still be possible, but you should treat the user experience impact as a platform requirement, not a post-launch surprise.

Which MEIDAYINGNUO module models are most suitable for platform standardization across multiple SKUs?

Once you define a stable display bay and interface baseline, model selection becomes an engineering matching exercise rather than a last-minute procurement decision. The real value of a platform-friendly module is consistent mechanics and integration behavior across a predictable socket, so your variants can scale features without reopening the display design.

MEIDAYINGNUO supports platform-style integration by aligning module selection with stable mechanical openings and controlled interface assumptions, then validating worst-case stack-up and enclosure behavior. For multi-SKU families, the goal is to choose a form factor that matches your shared window strategy and minimizes the need for per-version brackets, harnesses, or firmware exceptions.

| Clinical Role/Application | Usage Pattern | Display Requirements | Recommended Model | Key Integration Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bar-display platform across feature tiers | Frequent glance + status UI | Ultra-wide opening consistency | BU156X | Freeze window, datums, and connector corridor early |

| Larger bar-display platform across SKUs | Mixed interaction + telemetry | Ultra-wide bay with margin | BU215X | Reserve stack thickness and validate glare/readability targets |

| Square-display platform for multiple versions | Intermittent touch + menus | Stable square opening | SQ220S | Control bezel overlap and touch/cover thickness tolerance |

| Larger square-display platform scaling by screen size | Mixed interaction | Square opening family strategy | SQ332S | Keep datum scheme consistent; plan harness routing corridor |

| Indoor + semi-outdoor variants within one platform | Variable ambient light | Brightness headroom within one socket | HB215X | Validate worst-case thermal behavior and front-stack reflections |

FAQ

Can I keep the same LCD module if only the enclosure design changes?

Often yes, if the window opening, datum references, connector position, and front-stack space remain unchanged. Small enclosure tweaks can still break reuse if they alter bezel depth, cable routing, or thermal behavior.

What should I standardize first for successful multi-version reuse?

Standardize the mechanical display bay socket first: opening, datums, mounting points, and connector corridor. These are the slowest and most expensive constraints to change once multiple variants are in motion.

Will different cover glass or touch options break standardization?

They can. Stack thickness and surface reflections affect fit and perceived brightness, and they can change qualification scope. Standardization works best when you reserve space for the thickest stack and validate with the final front stack.

How do I prevent software from becoming a hidden standardization cost?

Freeze one interface and timing baseline, then manage differences with configuration profiles such as brightness curves, orientation, and UI scaling. Avoid per-version firmware forks unless the interface or power sequencing truly differs.

Is putting all variants on one module risky for supply chain?

Yes. A single disruption can halt every SKU. Mitigate with lifecycle planning, stocking strategy aligned to production ramps, and a pre-validated alternative that still fits your platform socket constraints.

When should I stop forcing “one module for all versions”?

When core constraints diverge: different openings, different interfaces, or fundamentally different environments that require different optical stacks or thermal limits. In those cases, two optimized modules can reduce risk and total cost versus a forced one-size approach.

Conclusion

Standardizing on one LCD module can save cost only when the platform is engineered for reuse: lock the display bay socket, interface baseline, thermal assumptions, and front-stack space early. Control differences through brackets, harness options, and configuration profiles, then validate the combined worst-case so performance and lifetime margins remain consistent across all SKUs.

MEIDAYINGNUO helps teams translate multi-version requirements into a stable display bay strategy, shortlist suitable module form factors, and plan worst-case validation for platform reuse. If you want to evaluate reuse feasibility for your device family, contact us using the email address below.

✉️ info@lcdmodulepro.com

🌐https://lcdmodulepro.com/

-

Understanding integration drift is crucial for managing design changes effectively and minimizing costs in engineering projects. ↩

-

This resource will provide insights into maintaining Interface Consistency for improved reliability and reduced testing efforts. ↩

-

Exploring solutions for these gaps can enhance product quality and reduce redesign efforts. ↩

-

Exploring thermal divergence will provide insights into managing heat in designs, enhancing reliability and user experience. ↩

-

Understanding cable routing constraints is crucial for ensuring product reliability and performance. Explore this link for expert insights. ↩